Author’s disclosure: I’m currently a Sr. Platform Architect at Pivotal, however I’ve written this article almost a whole year before joining the company. It is based on my own unsolicited experience working with the platform as a vendor for a third party.

I’ve been developing on Pivotal Cloud Foundry for several years. Working with the Spring boot stack, I was able to create CI/CD pipelines very easily and deployments were a breeze. I found it to be a truly agile platform (is that still a word in 2018?).

On the other hand, Kubernetes is gaining serious traction, so I’ve spent a few weeks trying to get a grasp on the platform. I’m in no means as experienced working with Kubenertes as I am in Cloud Foundry, so my observations are strictly as a novice to the platform.

In this article I will try to explain the differences between the two platforms as I see them from a developer’s perspective. There will not be a lot of internal under-the-hood architecture diagrams here, this is purely from a user experience point of view, specifically for a Java developer that is novice to either platform.

Such a comparison is also inherently subjective, so although I will try to provide objective comparison for any aspect, I will also give my personal thoughts on which aspect works best for me. These may or may not be conclusions you would agree with.

Overview

Cloud Foundry

Cloud Foundry is a cloud-agnostic platform-as-a-service solution. The open source cloud foundry is developed and supported by the cloud foundry foundation, which includes the likes of Pivotal, Dell EMC, IBM, VMWare, and many others. There are enterprise versions developed based on the open source project, such as IBM Bluemix and Pivotal Cloud Foundry (PCF for short).

Kubernetes

Kubernetes is an open source cloud platform that originated from Google’s Project Borg. It is sponsored by the Cloud Native Computing Foundation, whose members include top names of the industry such as AWS, Azure, Intel, IBM, RedHat, Pivotal and many others.

Kubernetes is first and foremost a container runtime. Although not limited to it, it is mostly used to run docker containers. There are several solutions that offer a PaaS experience on top of Kubernetes, such as RedHat OpenShift.

Similarities

- Both solutions use the idea of containers to isolate your application from the rest of the system.

- Both Cloud Foundry and Kubernetes are designed to let you run either on public cloud infrastructure (AWS, Azure, GCP etc.), or on-prem using solutions such as VMWare vSphere.

- Both solutions offer the ability to run in hybrid/multi-cloud environments, allowing you to spread your availability among different cloud providers and even split the workload between on-prem and public cloud.

- Starting with the latest release of Pivotal Cloud Foundry, both solutions support Kubernetes as a generic container runtime. More on that below.

PaaS vs IaaS+

Cloud Foundry

First and foremost, Cloud Foundry is a PaaS. I don’t feel Kubernetes fits this description. Some regard it as an IaaS+. Even Kubernetes’ own documentation describes itself as “not a traditional, all-inclusive PaaS”.

As a developer, the biggest differentiator for me is how Cloud Foundry takes a very Spring-like, opinionated approach to development, deployments and management.

If you ever used Spring Boot, you know that one of its strengths is the ability to auto-configure itself just by looking at your maven/gradle dependencies. For example, if you have a dependency on mysql JDBC driver, your Spring Data framework would auto-configure to use mysql. If no driver is provided, it would fallback to h2 in-memory database.

As we’ll see in this article, PCF seems to take a similar approach for application deployment and service binding.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes takes a different approach. It is inherently a generic container runtime that knows very little about the inner-workings of your application. Its main purpose is to provide a simple infrastructure solution to run your container, everything else is up to you as a developer.

Supported Containers

Kubernetes

Kubernetes runs Docker containers. As such, it supports a very wide range of applications, from a message broker to a Redis database to your own custom java application to anything you can find on Docker Hub.

Anyone who had a chance to write a Dockerfile knows it can be either a trivial task of writing a few lines of descriptor code, or it can get complicated rather quickly. Here’s a simple example I pulled off of github, and that’s a fairly simple example:

Running nodejs and Mongo DB in a docker container

This example should not seem intimidating to the average developer, but it does immediately show you there is a learning curve here. Since Docker is a generic container solution, it can run almost anything. It is your job as the developer to define how the operating system inside the container will execute your code. It is very powerful, but with great power comes great responsibility.

Cloud Foundry

Cloud Foundry takes a very opinionated approach to containers. It uses a container solution called garden. The original container in earlier versions of PCF was called warden, which actually predates docker itself.

Cloud foundry itself actually predates Kubernetes. The first release was in 2011, while kubernetes is available since 2014.

More importantly than the container runtime being used, is how you create a container.

Let’s take the example of a developer that needs to host a Spring Boot Java application.

With docker, you should define a Dockerfile to support running a java-based application. You can define this container in many different ways. You can choose different base operating systems, different JDK versions from different providers, you can expose different ports and make security assumptions on how your container would be available. There is no standard for what a java-based Spring Boot application container looks like.

In Cloud Foundry, you have one baseline buildpack for all java-based applications, and this buildpack is provided by the vendor. A buildback is a template for creating an application runtime in a given language. Buildpacks are managed by cloud foundry itself.

Cloud Foundry takes the guesswork that is part of defining a container out of the hands of the developer. It defines a “standard” for what a java-based container should look like, and all developers, devops teams and IT professionals can sync-up with this template. You can rest assured that your container will run just like other containers provided by other developers, either in your existing cluster or if you’ll move to a public cloud solution tomorrow.

Of course, sometimes the baseline is not enough. For example — you might want to add your own self-signed SSL certificates to the buildpack. You can extend the base buildpack in these scenarios, but that would still allow you to use a shared default as the baseline.

Continuing with the opinionated approach, Cloud foundry can identify which buildpack to use automatically, based on the contents of the provided build artifact. This artifact might be a jar file, a php folder, a nodejs folder, a .NET executable etc. Once identified, cloud foundry will create the garden container for you.

All this means that with PCF, your build artifact is your native deployment artifact, while in Kubernetes your build artifact is a docker image. With Kubernetes, you need to define the template for this docker image yourself in a Dockerfile, while in PCF you get this template automatically from a buildpack.

Management Console

Cloud Foundry

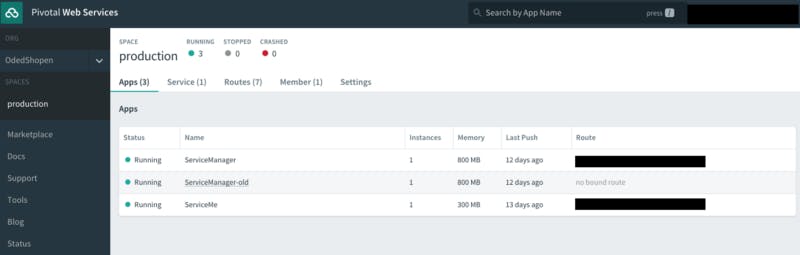

PCF separates the web dashboard to two separate target audiences.

Ops Manager is targeted at the IT professional that is responsible for setting up the virtual machines or hardware that will be used to create the PCF cluster.

Apps Manager is targeted at the developer that is responsible for pushing application code to testing or production environments. The developer is completely unaware of the underlying infrastructure that runs its PCF cluster. All he can really see is the quotas assigned to his organization, such as memory limits.

Kubernetes

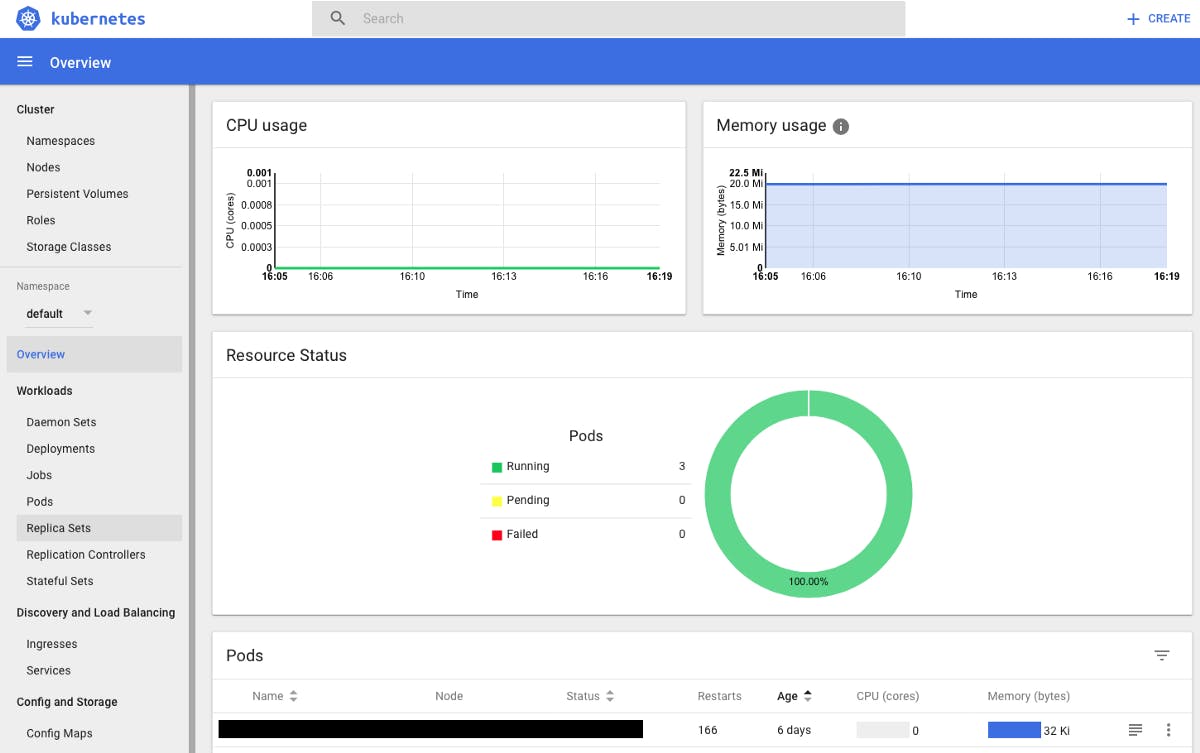

Kubernetes takes a different approach. You get one dashboard to manage everything. Here’s a typical Kubernetes dashboard:

As you can see from the left-hand side, there is a lot of data to process here. You have access to persistent volumes, daemons, definition of roles, replication controllers etc. It’s hard to focus on what are the developer’s needs and what are the IT needs. Some might tell you this is the same person in a Devops culture, and that’s a fair point. Still, in reality-it is a more confusing paradigm compared to a simple application manager.

Command Line Interface

Cloud Foundry

Cloud foundry uses a command line interface called cf. It is a cli that lets you control all aspects of the developer interaction. Following in the footsteps of simplicity that you might have already noticed, the idea is to take an opinionated view to practically everything.

For example, if you are in a folder that contains a spring boot jar file called myapp.jar, you can deploy this application to PCF with the following command:

cf push myapp -p myapp.jar

That’s it! That’s all you need. PCF will lookup the current working directory and find the jar executable. It will then update bits to the platform, where the java buildpack would create a container, calculate the required memory settings, deploy it to the currently logged-in org and space in PCF, and set a route based on the application name:

wabelhlp0655019:test odedia$ **cf push myapp -p myapp.jar**

Updating app myapp in org OdedShopen / space production as user…

OK

Uploading myapp…

Uploading app files from: /var/folders/\_9/wrmt9t3915lczl7rf5spppl597l2l9/T/unzipped-app271943002

Uploading 977.4K, 148 files

Done uploading

OK

Starting app myapp in org OdedShopen / space production as user…

Downloading pcc\_php\_buildpack…

Downloading binary\_buildpack…

Downloading python\_buildpack…

Downloading staticfile\_buildpack…

**Downloading java\_buildpack…

**Downloaded binary\_buildpack (61.6K)

Downloading ruby\_buildpack…

Downloaded ruby\_buildpack

Downloading nodejs\_buildpack…

Downloaded pcc\_php\_buildpack (951.7K)

Downloading go\_buildpack…

Downloaded staticfile\_buildpack (7.7M)

Downloading ibm-websphere-liberty-buildpack…

Downloaded nodejs\_buildpack (111.6M)

Downloaded ibm-websphere-liberty-buildpack (178.4M)

Downloaded java\_buildpack (224.8M)

Downloading php\_buildpack…

Downloading dotnet\_core\_buildpack…

Downloaded python\_buildpack (341.6M)

Downloaded go\_buildpack (415.1M)

Downloaded php\_buildpack (341.7M)

Downloaded dotnet\_core\_buildpack (919.8M)

**Creating container

Successfully created container

**Downloading app package…

Downloaded app package (40.7M)

Staging…

— — -> Java Buildpack Version: v3.18 |

[https://github.com/cloudfoundry/java-buildpack.git#841ecb2](https://github.com/cloudfoundry/java-buildpack.git#841ecb2)

— — -> Downloading Open Jdk JRE 1.8.0\_131 from [https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/openjdk/trusty/x86\_64/openjdk-1.8.0\_131.tar.gz](https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/openjdk/trusty/x86_64/openjdk-1.8.0_131.tar.gz) (found in cache)

Expanding Open Jdk JRE to .java-buildpack/open\_jdk\_jre (1.1s)

— — -> Downloading Open JDK Like Memory Calculator 2.0.2\_RELEASE from [https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/memory-calculator/trusty/x86\_64/memory-calculator-2.0.2\_RELEASE.tar.gz](https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/memory-calculator/trusty/x86_64/memory-calculator-2.0.2_RELEASE.tar.gz) (found in cache)**Memory Settings: -Xmx681574K -XX:MaxMetaspaceSize=104857K -Xss349K -Xms681574K -XX:MetaspaceSize=104857K**

— — -> Downloading Container Security Provider 1.5.0\_RELEASE from [https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/container-security-provider/container-security-provider-1.5.0\_RELEASE.jar](https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/container-security-provider/container-security-provider-1.5.0_RELEASE.jar) (found in cache)

— — -> Downloading Spring Auto Reconfiguration 1.11.0\_RELEASE from [https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/auto-reconfiguration/auto-reconfiguration-1.11.0\_RELEASE.jar](https://java-buildpack.cloudfoundry.org/auto-reconfiguration/auto-reconfiguration-1.11.0_RELEASE.jar) (found in cache)

Exit status 0

Uploading droplet, build artifacts cache…

Uploading build artifacts cache…

Uploading droplet…

Staging complete

Uploaded build artifacts cache (109B)

**Uploaded droplet (86.2M)

**Uploading complete

Destroying container

Successfully destroyed container

0 of 1 instances running, 1 starting

0 of 1 instances running, 1 starting

0 of 1 instances running, 1 starting

0 of 1 instances running, 1 starting

**1 of 1 instances running**

Although you can start with barely any intervention, this doesn’t mean you give up any control. You have a lot of customizations available in PCF. You can define your own routes, set the number of instances, max memory and disk space, environment variables etc. All of this can be done in the cf cli or by having a manifest.yml file available as a parameter to the cf push command. A typical manifest.yml file can be as simple as the following:

applications:

\- name: my-app

memory: 512M

instances: 2

env:

PARAM1: PARAM1VALUE

PARAM2: PARAM2VALUE

The main takeaway is this: with PCF, provide the information you know, and the platform will imply the rest. Cloud Foundry’s haiku is:

Here’s my code

Run it on the cloud for me.

I don’t care how.

Kubernetes

In Kubernetes, you interact with the kubectl cli. The commands are not complicated at all, but there is still a higher learning curve from what I’ve experienced so far.

For starters, a basic assumption is that you have a private docker registry available and configured (unless you only plan to deploy images available on public registries such as docker hub). Once you have that registry up and running, you will need to push your Docker image to that registry.

Now that the registry contains your image, you can initiate commands to kubectl to deploy the image. Kubernetes documentation gives the example of starting up an nginx server:

*# start the pod running nginx*

**$ kubectl run --image=nginx nginx-app --port=80 --env="DOMAIN=cluster"

**deployment "nginx-app" created

The above command only spins up a kubernetes pod and runs the container.

A pod is an abstraction that groups one or more containers to the same network ip and storage. It’s actually the smallest deployable unit available in Kubernetes. You can’t access a docker container directly, you only access its pod. Usually, a pod would contain a single docker container, but you can run more. For example, an application container might want to have some monitoring dameon container in the same pod.

In order to make the container accessible to other pods in the Kubernetes cluster, you need to wrap the pod with a service:

*# expose a port through with a service*

**$ kubectl expose deployment nginx-app --port=80 --name=nginx-http

**service "nginx-http" exposed

Your container is now accessible inside the kubernetes cluster, but it is still not exposed to the outside world. For that, you need to wrap your service with an ingress.

Note: Ingress is still considered a beta feature!

I could not find a simple command to expose an ingress at this point (please correct me if I’m wrong!). It appears that you must create an ingress descriptor file first, for example:

**apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: test-ingress

annotations:

ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: /

spec:

rules:

- http:

paths:

- path: /testpath

backend:

serviceName: test

servicePort: 80**

Once that file is available, you can create the ingress by issuing a command

kubectl create -f my-ingress.yaml

Note that unlike the single manifest.yml in PCF, the deployment yml files in Kubernetes are separated — there is one for pod creation, one for service creation and as you saw above — one for ingress creation. A typical descriptor file is not entirely overwhelming but I wouldn’t call it the most user friendly either. For example, here’s a descriptor file for nginx deployment:

apiVersion: apps/v1 # for versions before 1.9.0 use apps/v1beta2

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: nginx-deployment

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: nginx

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: nginx

spec:

containers:

- name: nginx

image: nginx:1.7.9

ports:

- containerPort: 80

All this to say — with Kubernetes, you need to be specific. Don’t expect deployments to be implied. If I had to create a haiku for Kubernetes, it’ll be probably something like this:

Here’s my code

I’ll tell you exactly how you should run it on the cloud for me

And don’t you dare make any assumptions on the deployment without my written consent!

Zero Downtime Deployments

Both platforms support the ability to deploy applications with zero downtime, however this is one area where Kubernetes wins in my opinion, since it provides a built-in mechanism for zero downtime deployments with rollback.

2019 update: As of Pivotal Cloud Foundry 2.4, native zero-downtime deployments are available out of the box!

Cloud Foundry

With Pivotal Cloud Foundry, t̶h̶e̶r̶e̶’̶s̶ ̶n̶o̶ ̶b̶u̶i̶l̶t̶-̶i̶n̶ ̶m̶e̶c̶h̶a̶n̶i̶s̶m̶ ̶t̶o̶ ̶s̶u̶p̶p̶o̶r̶t̶ ̶a̶ ̶r̶o̶l̶l̶i̶n̶g̶ ̶u̶p̶d̶a̶t̶e̶, you’re basically expected to do some cf cli trickery to perform the update with zero downtime. The concept is called blue-green deployment. If I had to explain it in step-by-step guide, it’ll probably be something like this:

- Starting point: you have myApp in production, and you want to deploy a new version of this app — v2.

- Deploy v2 under a new application name, for example — myApp-v2

- The new app will have its own initial route — myApp-v2.mysite.com

- Perform testing and verification on the new app.

- Map an additional route to the myApp-v2 application, using the same route as the original application. For example:

cf map-route myApp-v2 mysite.com —hostname myApp

- Now requests to your application are load balanced between v1 and v2. Based of the number of instances available to each version, you can perform A/B testing. For example — if you have 4 instances of v1 and 1 instance of v2, 20% of your clients will be routed to the new codebase.

- If you identify issues at any point — simply remove v2. No harm done.

- Once you are satisfied, scale the number of available instances of v2, and reduce or completely delete the instances of v1.

- Remove the myApp-v2.mysite.com route from v2 of your application. You have now fully migrated to the new codebase with zero downtime, including sanity testing phase and potentially A/B testing phase.

Note: The cf cli supports plugin extensions. Some of them provide automated blue-green deployments, such as blue-green-deploy, autopilot and zdd. I personally found blue-green-deploy to be very easy and intuitive, especially due to its support for automated smoke tests as part of the deployment.

Kubernetes

kubectl has a built-in support for rolling updates. You basically pass a new docker image for a given deployment, for example:

kubectl set image deployments/kubernetes-bootcamp kubernetes-bootcamp=jon/kubernetes-bootcamp:v2

The command above tells kubernetes to perform a rolling update between all pods of the kubernetes-bootcamp deployment from its current image to the new v2 image. During this rollout, your application remains available.

Even more impressive — you can always revert back to the previous version by issuing the undo command:

kubectl rollout undo deployments/kubernetes-bootcamp

External Load Balancing

As we saw previously, both PCF and Kubernetes provide load balancing for your application instances/pods. Once a route or an ingress is added, your application is exposed to the outside world.

If we’ll take an external view of the levels of abstraction that are needed to reach your application, we can describe them as follows:

Kubernetes

ingress → service → pod → container

Cloud Foundry

route → container

Internal Load Balancing (Service Discovery)

Cloud Foundry

PCF supports two methods of load balancing inside the cluster:

- Route-based load balancing, in the traditional server-side configuration. This is similar to external load balancing mentioned above, however you can specify certain domains to only be accessible from within PCF, thereby making them internal.

- Client side load balancing by using Spring Cloud Services. This set of services offers features from the Spring Cloud frameworks that are based on Netflix OSS. For service discovery, Spring Cloud Services uses Netflix Eureka.

Eureka runs as its own service in the PCF environment. Other applications register themselves with Eureka, thereby publishing themselves to the rest of the cluster. Eureka server maintains a heartbeat health check of all registered clients to keep an up-to-date list of healthy instances.

Registered clients can connect to Eureka and ask for available endpoints based on a service id (the value of spring.application.name in case of Spring Boot applications). Eureka would return a list of all available endpoints, and that’s it. It is up to the client to actually access one of these endpoints. That is usually done using frameworks like Ribbon or Feign for client-side load balancing, but that is an implementation detail of the application, and not related to PCF itself.

Client-side load balancing can theoretically scale better since each client keeps a cache of all available endpoints, and can continue working even if Eureka is temporarily down.

If your application already uses Spring Cloud and the Netflix OSS stack, PCF fits your needs like a glove.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes uses DNS resolution to identify other services within the cluster. Inside the same namespace, you can lookup another service by its name. In another namespace, you can lookup the service’s name followed by a dot and then the other namespace.

The major benefit that Kubernetes’ load balancing offers is not requiring any special client libraries. Eureka is mostly targeted at java-based applications (although solutions exist for other languages such as Steeltoe for .NET). With Kubernetes, you can make load-balanced http calls to any Kubernetes service that exposes pods, regardless of the implementation of the client or the server. The load-balancing domain name is simply the name of the service that exposes the pods. For example:

- You have an application called my-app in namespace zone1

- It exposes a GET /myApi REST endpoint

- There are 10 pods of this container in the cluster

- You created a service called my-service that exposes this application to the cluster

- From any other pod inside the namespace, you can call:

GET https://my-service/myApi

- From any other pod in any other namespace in the cluster, you can call:

GET https://my-service.zone1/myApi

And the API would load-balance over the available instances. It doesn’t matter if your client is written in Java, PHP, Ruby, .NET or any other technology.

2018 update: Pivotal Cloud Foundry now supports polyglot, platform-managed service discovery similar to Kubernetes, using Envoy proxy, apps.internal domain and BOSH DNS.

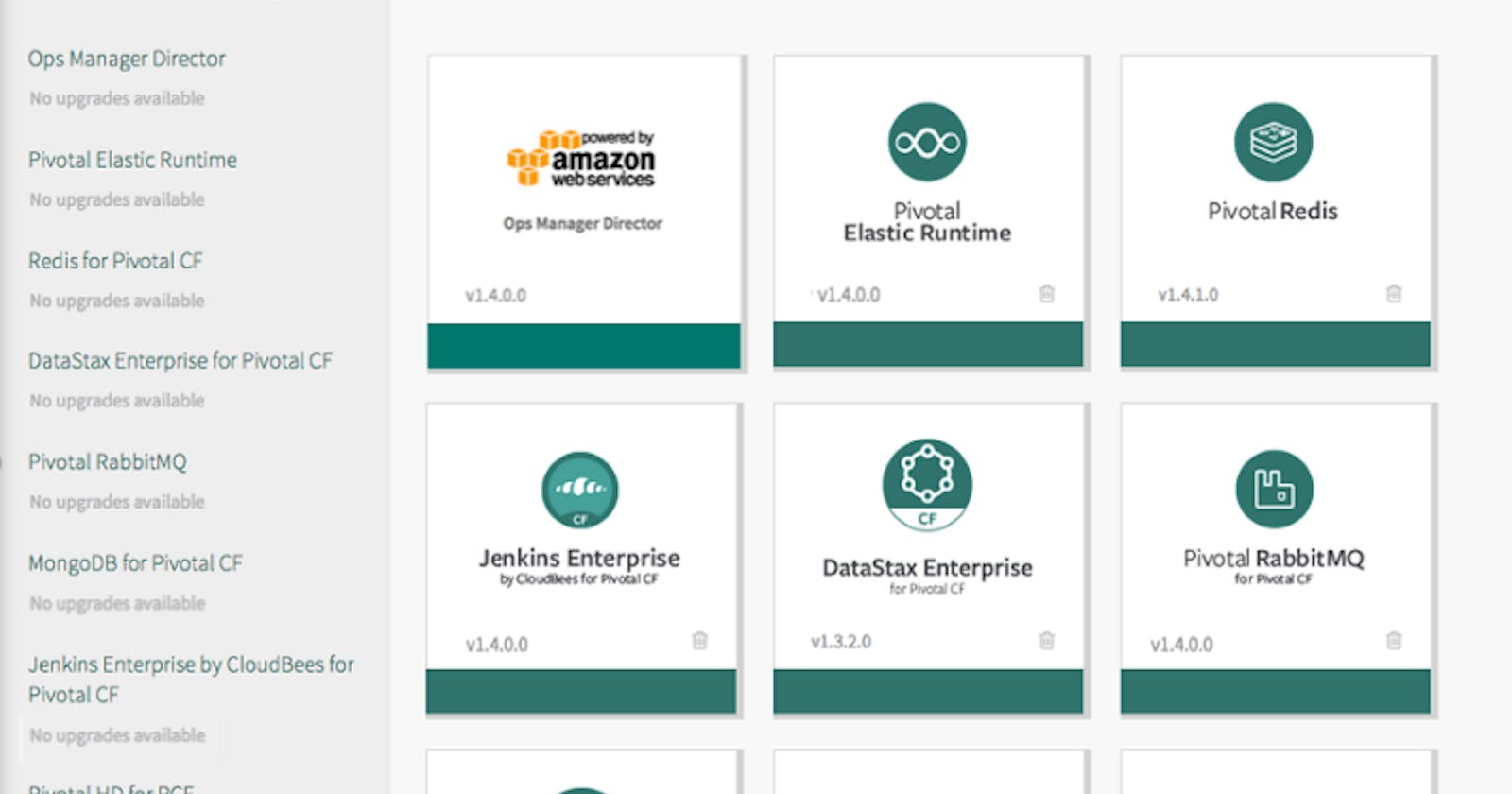

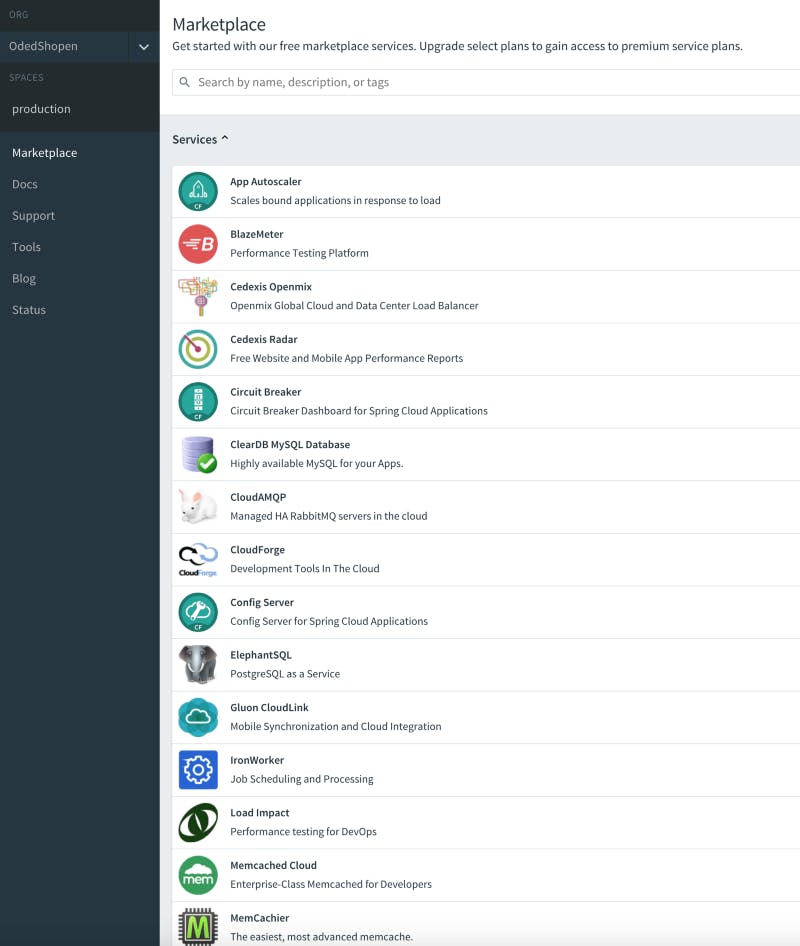

Marketplace

PCF offers a services marketplace. It provides a ridiculously simple way to bind your application to a service. The term service in PCF is not the same as a service in kubernetes. A PCF service binds your application to things like a database, a monitoring tool, a message broker etc. Some example services are:

- Spring Cloud Services, which provides access to Eureka, a Config Server and a Hystrix Dashboard.

- RabbitMQ message broker.

- MySQL.

Third party vendors can implement their own services as well. Some of the vendor offerings include MongoDB Enterprise and Redislabs for Redis in-memory database. Here’s a screenshot of available services on Pivotal Web Services:

IBM Bluemix is another Cloud Foundry provider that offers its own services such as IBM Watson for AI and machine learning applications.

Every service has different plans available based on your SLA needs, such as a small database for development or a highly-available database for a production environment.

Last but not least, you have the option to define user-provided services. These allow you to bind your application to an existing service that you already have, such as an Oracle database or an Apache Kafka message broker. A user provided service is simply a group of key-value pairs that you can then inject into your application as environment variables. This offloads any specific configuration such as URLs, usernames or passwords to the environment itself — services are bound to a given PCF space.

Kubernetes

Kubernetes does not offer a marketplace out of the box. There is a service catalog extension that allows for a similar service catalog, however it is still in beta.

Note that since it can run any docker container — Dockerhub can be considered as a kubernetes marketplace in a way. You can basically run anything that can run in a container.

Kubernetes does have a concept similar to user-provided services. Any configuration or environment variables can exist in ConfigMaps, which allow you to externalise configuration artifacts away your container, thus making it more portable.

Configuration

Speaking of configuration — One of the features of the Spring Cloud Services service is Spring Cloud Config. It is another service that is targeted specifically for Spring Boot applications. The config service serves configuration artifacts from a git repository of your choosing, and allows for zero-downtime configuration changes. If your Spring beans are annotated with @RefreshScope, they can be reloaded with updated configuration by issuing a POST /refresh API call to your application. The property files that are available as configuration sources are loaded based on a pre-defined loading order, which provides some sort of an inheritance-based mechanism to how the configuration is loaded. It’s a great solution, but again assumes that your applications are based on the Spring Cloud (or .NET Steeltoe) stack. If you’re already using spring boot with a config server today — PCF fits like a glove.

In Kubernetes, you can still run a config server as a container, but that would probably become an unneeded operational overhead since you already have built-in support for ConfigMaps. Use the native solution for the platform you go with.

Storage Volumes

A big differentiator of Kubernetes is the ability to attach a storage volume to your container. Kubernetes uses etcd as a means to manage storage volumes, and you can attach such a volume to any of your containers. This means you get a reliable storage solution, which lets you run storage-based containers like a database or a file server.

In PCF, your application is fully stateless. PCF follows the 12-factor apps model and one of these models assumes that your application has no state. You should theoretically take the same application that runs today in your on-prem data center, move it to AWS, and provided there is adequate connectivity, it should just work. Any storage-based solution should be offloaded to either a PCF service, or to a storage solution outside the PCF cluster itself. This may be regarded as an advantage or a disadvantage depending on your application and architecture. For stateless application runtimes such as web servers, it is always a good idea to decouple it from any internal storage facility.

Onboarding

Kubernetes

Getting started with Kubernetes was not easy. As mentioned above, you can’t just start with a 5-minutes quick start guide, there are just too many things you need to know and too many assumptions about what you already have (docker registry and a git repository are often taken for granted).

Just taking a look at the excellent Kubernetes Basics interactive tutorial shows the level of knowledge required on the platform. For a basic on-boarding, there are 6 steps, each one of them containing quite a few commands and terminologies you need to understand. Trying to follow the tutorial on a local minikube vm instead of the pre-configured online cluster is quite difficult.

Cloud Foundry

Getting started with PCF is easy. Your developers already know how to develop their spring boot / nodejs / php / ruby / .NET application. They already know what its artifacts are. They probably already have some jenkins pipeline in place. They just want to run the same thing in a cloud environment.

If we’ll take a look at PCF’s “Getting Started with Pivotal Cloud Foundry”, it’s almost comical how little is required to get something up and running. When you need more complex interaction, it’s all available for you, either in the cf cli, as part of a manifest.yml, or in the web console, but this doesn’t prevent you from getting started quickly.

If you mainly develop server-based applications in java or nodejs, PCF gets you to the cloud simply, quickly and more elegantly.

Vision

Kubernetes

Kubernetes is truly a great open source platform. Kudos to Google for giving up control and letting the community do its thing. That’s probably the number one reason why Kubernetes has taken off so quickly while other solutions like Docker swarm are falling behind. Other vendors also offer solutions that offer a more PaaS-like experience on top of Kubernetes, such as RedHat OpenShift.

But with such a diverse and thriving eco-system, the path forward can be one of many different directions. It really does feel like a Google product in a way — maybe it will remain supported by Google for years, maybe it will change with barely any backwards compatibility, or maybe they’ll kill it and move to the next big thing (Does anyone remember Google Buzz, Google Wave or Google Reader?). Any AngularJS developer who’s trying to move to Angular 5 can tell you that backwards compatibility is not a top priority.

Cloud Foundry

Cloud Foundry is also a thriving open source platform, but it is pretty clear who sets the tone here. It is Pivotal, with additional contributions from IBM. Yes, it’s open source, but the enterprise play here is Pivotal Cloud Foundry, which provides added value like the services marketplace, Ops Manager etc. And on that side, it’s a limited democracy. This is a product that is meant to serve enterprise customers, and the feature set would first and foremost answer those needs.

If Kubernetes is Google, then PCF is Apple.

A little more of a walled garden, more controlled, better design/experience layer, and a commitment for delivering a great product. I feel like the platform is more focused, and focus is critical in my line of work.

PKS

The real surprise of the recently announced PCF 2.0 was that all I’ve been talking about throughout this article is now just one part of a larger offering. The application runtime (everything that is referred to as PCF in this article) is now called Pivotal Application Service (PAS). There is also a new serverless solution called Pivotal Function Service (PFS), and lastly — a new Kubernetes runtime called Pivotal Container Service (PKS). This means that Pivotal Cloud Foundry now gives you the best of both worlds: A great application runtime for fast onboarding of cloud-native applications, as well as a great container runtime when you need to develop generic low-level containers.

Conclusion

In this article I tried to share my personal experiences of working with both platforms. Although I am a bit biased towards PCF, it is for a good reason — it has served me well. I approached Kubernetes with an open mind, and found it to be a very versatile platform, but also one that requires a steeper learning curve. Maybe I got spoiled by living in the Spring eco-system for too long :). With the latest announcement of PKS, it appears that Pivotal Cloud Foundry is set to offer the best integrated PaaS — one that lets you run cloud native applications as quickly and simply as possible, while also exposing the best generic container runtime when that is needed. I can see this becoming very useful in many scenarios. For example, Apache Kafka is one of the best message brokers available today, but this message broker still doesn’t have a PCF service available, so it has to run externally on virtual machines. Now with PCF 2.0, I can run Apache Kafka in docker containers inside PCF itself.

The main conclusion is that this is definitely not a this or that discussion. Since both the application runtime and the container runtime now live side by side in the same product, the future seems promising for both.

Thank you for reading, and happy coding!

Oded Shopen

Visit my homepage: odedia.org

Follow me on twitter: twitter.com/odedia

Follow me on LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/odedia

Follow me on 500px: https://500px.com/odedia