Software is eating the world.

Companies large and small are going through a digital transformation journey, as they try to compete in this age of digital disruption. It’s no longer big-fish-eats-small-fish. We’re in a fast-fish-eats-slow-fish world.

One particular development architecture is dominating the discussion: Microservices.

What are microservices again?

If you’re reading this article, you’re probably familiar with the microservice architecture in some shape or form. Still, it’s nice to occasionally go back to basics and try to define what we are trying to achieve.

I like Chris Richardson’s definition of microservices at microservices.io:

“The microservice architecture is an architectural style that structures an application as a collection of loosely coupled services, which implement business capabilities. The microservice architecture enables the continuous delivery/deployment of large, complex applications. It also enables an organisation to evolve its technology stack.”

The definition is a set of ideas and patterns. It doesn’t talk about how the architecture is implemented. If you’ll read it again, you’ll notice that you should be able to implement the microservice architecture inside a monolith. It can have logical services as well, right?

If we’ll drill down to actual implementations, we’ll find that usually, microservices are implemented as separate processes that communicate over lightweight protocols such as HTTP or messaging, using interfaces written in JSON. Why do we use such implementations instead of implementing the microservice architecture inside our monoliths? In my opinion, it’s because it is hard for us as humans to identify the silos and boundaries while working with large systems. Breaking it apart to smaller, more manageable pieces lets us focus on a single problem domain and add additional safety nets around our work.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit: the title of this article is a bit of a link bait. It does however try to explain the premise of this article: Based on my own personal experience, I believe that microservices have a more profound organisational and cultural impact that a technological impact. There are definitely technological benefits, and I’ll mention some of them, but I find the most valuable benefits beyond the technology stack.

Also, I should point out that when I’m talking about monoliths and their drawbacks in this article, I am referring to existing, legacy monoliths that you might find at large organisations. If you were to start a new monolith today, you could avoid many of the pitfalls I’ll describe. Due to the nature of the monolith architecture, it will probably be harder to maintain the same level quality over time, since the architecture doesn’t provide any guardrails to prevent developers from making mistakes.

Technological benefits of microservices

The microservice architecture does have technological advantages. In my view, the main technological advantage of the microservice architecture is the ability to scale each microservice in isolation, based on its specific load requirements. This achieves an optimal utilisation of the compute resources at hand. You don’t have to over-scale components that do not require it.

Another benefit is the ability to selectively deploy only those microservices that change, and not the entire application.

Technological drawbacks of microservices

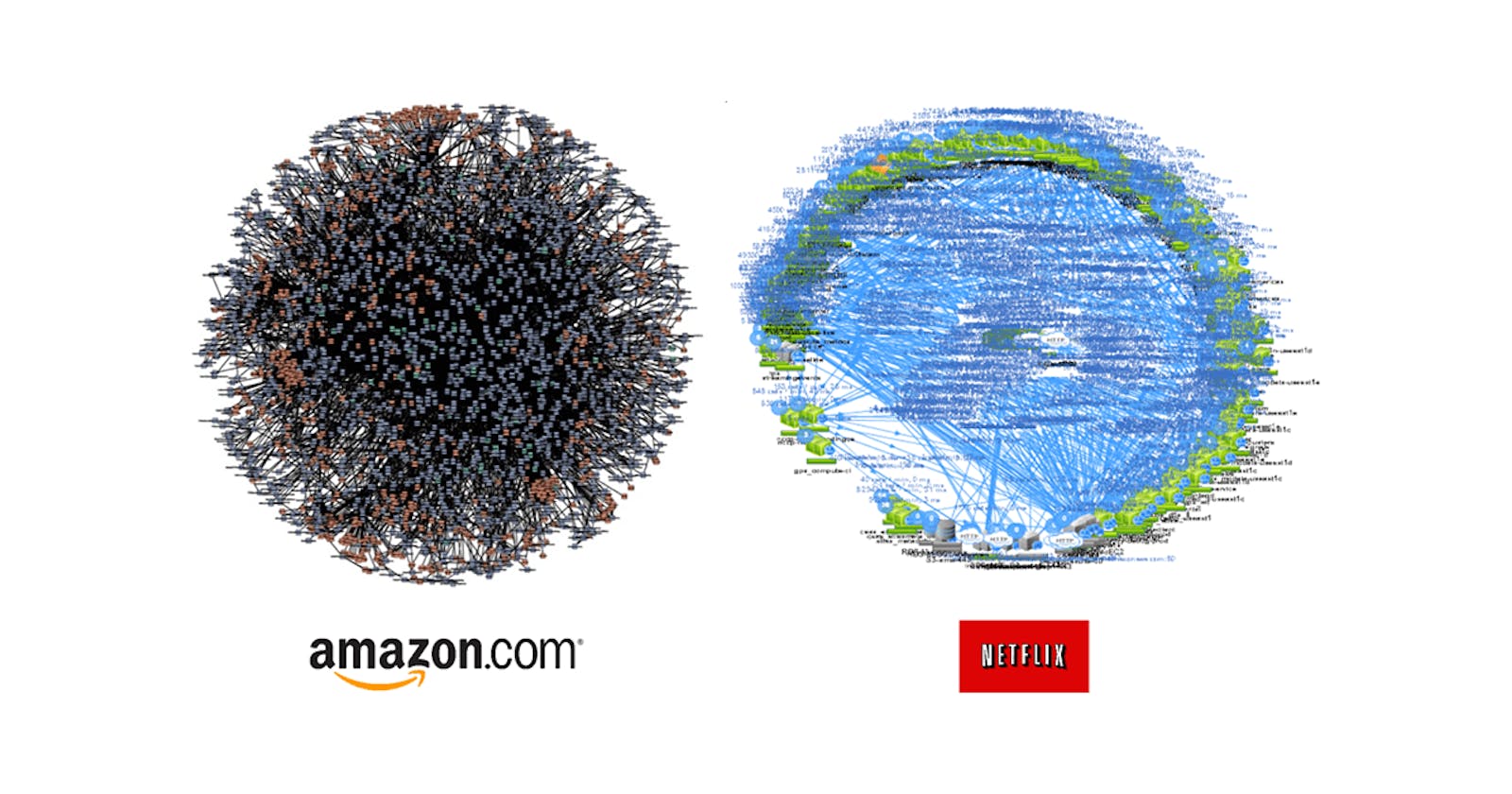

The microservice architecture is a distributed system architecture. Distributed systems are hard. There are quite a few operational concerns to think about when managing a distributed system at scale, that simply don’t exist in the monolith world. For example, tracing end-to-end flows becomes a challenge. Your in-process call stack is replaced with network calls that have latency. Call failures can result in subsequent cascading failures.

A good summary of the problems with managing distributed systems

Many design patterns have emerged to overcome some of those drawbacks. Books were written to help developers and operational teams design and monitor microservices at scale. Service registry, circuit breakers, externalised configuration, API gateway, the SAGA pattern, eventual consistency — all of these were designed to overcome the shortcomings of a microservice architecture compared to that of a monolith. Why would anyone choose to go down that path? Isn’t it easier to just over-scale your monolith and be done with it?

The main reason for going to a microservice architecture is not necessarily a technological one, because there are quite a few technological drawbacks to deal with as well. The main reason, in my mind, is to improve process, culture and developer focus. I’ll provide some examples in the rest of this article.

Organisational benefits of microservices

Focus on a single project

News flash: developers don’t like to stare at a project with 5,000 classes and 1 million lines of code. Who would? Information overload is a serious problem in large organisations. I remember projects where on-boarding for new developers was estimated at almost 4 months. That’s 4 months of an organisation investing in the developer, without getting much value. During that time, the developer can easily become frustrated or just plain bored. It’s not fun to constantly approach your fellow colleagues with endless questions, trying to understand what a specific class does, or how changing it impacts the rest of the system. It is quite possible that some of these developers would just give up and look for another job.

Now, imagine that same developer coming into a project with 200 classes and a few thousands lines of code. The entire source code can be read in a day or two. The documentation for the project — if needed at all — is short and to the point. The project exposes just a few APIs, listens to 2–3 topics on a Kafka message broker, and performs 2 REST API calls to other microservices in the system. The database for the microservice has 12 tables.

Which project would you prefer to work on? I know which one I’d pick. Sure, in a perfect organisation you could achieve similar structure in a well-designed monolith, but for some unknown reason, human behaviour keeps creeping into the development lifecycle. Funny how that is.

Smaller Code Repositories

Git is awesome, once you get the hang of it. After a couple of months.

Still, no source control repository can completely solve the human factor. Think about hundreds of developers touching the same codebase, where you might have some pesky “global” classes that define utilities, shared data types or abstract classes. Eventually, developers will step on each other’s toes. They’ll need to understand if their merge should override the other developer’s code. If they’re good developers, they’ll have a discussion amongst themselves and decide on the right solution, thus wasting valuable time. If they are not so great, they’ll just override the code.

I can see how some of you are nodding your heads in disbelief, thinking I just don’t get how proper development is done. Well, guess what? Not all developers are the same. Some are rock-stars, some are great, some are ok, some are less-than-ok. You need to a development pipeline that serves them all. Who said they’re even using git? It’s quite possible they are using a solution like Perforce, CVS, Microsoft SourceSafe, or — god forbid — some home-grown SCM. I’ve seen those. They exist.

In the microservice architecture, each microservice lives in its own repository. This repository can be a separate git repository, or a separate folder-per-project in a bigger git repository. I personally prefer the former, since you don’t need to constantly pull code you’re not working on and it provides a clear separation.

Regardless of your definition for a repository, you’re eventually working on a smaller codebase. The development team is small, and hopefully co-located. The chance of stepping on each other’s toes is less frequent.

Could you have achieved the same separation of repositories with a monolith? Sure! How many organisations can really enforce this properly? Not many. Eventually, the codebase will grow.

Parallel development with clear boundaries

Sharing your code repository is just one part of the problem. Another one is the wait game. My team’s code is dependent on a service written by another team. That team has more work to be done, and they haven’t finished development yet. Even though the sprint started out great and everyone were on track, those pesky human factors kept creeping in once again. One of the lead developers got sick. The DBA took its time changing the database schema in the development environment. There is always a reason.

In a monolith, sometimes my code actually calls a method of the other team directly, within the same process. It can be done through interfaces and dependency injection to reduce the coupling between the two, but if the target implementation is not done I have to wait for it. A team might decide to eventually create temporary methods/beans to simulate the responses. It can quickly become messy.

The single process could also mean a shared build lifecycle. In such a case, if team B broke the build then team A has to wait for them to fix it before they can run another build.

To clarify, monoliths don’t have to behave this way. Team A and team B can develop separate modules that eventually create the final deployment artifact, so the build process can be separated. A monolith can implement in-process eventing to avoid direct method calls. For older systems, even good-old Local EJBs can achieve some level of improved decoupling. In reality, though, the boundaries tend to get more vague simply because my codebase is aware of the codebase developed by the other team. It’s harder to enforce the separation of concerns.

In the microservice architecture, the codebase is broken into two different processes. By default, you don’t see the other team’s code and implementation. Your communication channel is the interface that you both agreed on. Some teams may use strict interfaces using Swagger or JSON schema, others may use a more lightweight approach. Regardless of the interface, the communication channel is no longer in-process. Making changes to the implementation of team B doesn’t require rebuilding the implementation of team A. Your developers are not exposed to the internal intricacies of the other team. Similar to how Java encapsulation hides away private methods and fields, the microservice architecture hides the implementation that is not your responsibility so you can focus on yours.

Experimentation

Changing existing code in a monolith is scary. Let’s be honest, you probably don’t have enough test coverage for your 15-year old application. Now there is a requirement that means you have to change a method that you know is being invoked from pretty much everywhere. Your hands tremble as you type, don’t they?

Limiting the scope of failure to a single microservice is a technological benefit for the application as a whole. If you have circuit breakers in place, you can probably survive the occasional failure.

However, it is also a reassuring benefit to the person writing the code. Knowing that your change will at worst bring down your particular service and not the entire production environment will allow you to sleep better at night. It also lets you experiment more easily with new ideas and features. Most modern cloud environments allow you to rollback to a previous version of a container quickly and easily. If you made a mess, it’s doesn’t have to be the end of the world. Such a mindset allows organisations to go faster. Faster means responding more quickly to change.

Polyglot Microservices

Are you using Java? How long did it take you to upgrade from Java 7 to 8? That must have been a fun production night, wasn’t it? Perhaps you’re using the .NET Framework and consider moving from version 4.0 to 4.5, or maybe even consider moving to .NET Core (good idea, by the way).

If making a framework upgrade means impacting every single aspect of your production deployment, it is highly unlikely that the business would agree to it. The risk just isn’t worth it. Usually such a change occurs when existing framework versions are no longer supported by the vendor. That means you have to move to newer versions when you have no choice. Now you add pressure to the mix. That’s never a good thing.

With microservices, this is less of a concern. New microservices can use the latest and greatest frameworks from day one. Older microservices can be upgraded one by one, when you see fit. If there are issues, they will not bring down the entire production environment and would be limited to the particular microservice.

Your microservices are polyglot. Communication is done via language-agnostic protocols such as HTTP or messaging, which means each microservice can be written in a different language or framework, running on different operating systems — it all depends on what makes sense for the particular use case. Granted, you don’t want to support 10 different languages and 20 frameworks, but at least you have choice when it’s needed.

Developer excitement

Developers like to explore new technologies. It’s probably why they chose a career in software development in the first place. If all development is done using EJBs on IBM WebSphere, it is likely you will not be able to hire the best candidates fresh out of college. However, if you’re using Spring Boot, explore some reactive programming in one or two microservices, develop UI using Angular or React, maybe add some Go and Python where it makes sense — now you got developers interested. Some will want to work on modern UI, some will want to focus on the backend, others will choose batch or event-driven applications. Your developers are different individuals, and they are most productive when they are passionate about their work.

Choice of isolated data services

Let’s face it. Just like there are no silver bullets for any given architecture, there are no silver bullets for your backing data services. You probably don’t want to hold session state in an Oracle DB. You probably don’t want to use MySQL for a DIY messaging solution using some polling technique. You probably don’t want to use Cassandra if you think you’ll need foreign keys. Every database has benefits as drawbacks. You need the right tool for the job. “It Depends”.

With a monolith architecture, the database tends to grow with the monolith application and become a monolith by itself. You might add a caching service or a message broker, but your system of record is usually a single system, and your DBA spends a lot of time optimising and partitioning the database to support the massive amounts of data you store.

Once you picked a data source, you will probably not change it. Just look how many organisations still have to use Oracle database. Sure, it’s a very good database, but it’s also a proprietary, expensive database. Many organisations would love to switch to cheaper solutions. Yet, even giants like Amazon can’t completely let go of this dependency, due to decisions they made many years ago — probably the right decision at the time. Recently, Amazon said they would stop using Oracle completely, and even they have to invest around two years and a considerable amount of effort to get there. How do you think your organisation will do?

Does it have to be this way? Of course not. A monolithic database can be broken into multiple schemas. In its most basic form, I’ve seen many cases of separating the reference data from the application data. You can build a monolith with the right database design, or even a monolith with multiple databases. However, for many existing monoliths in existing organisations, that is not the case. The architecture probably did not impose the clear schema boundaries when the system was built, which led to the database becoming somewhat of a monolith in its own right.

In the microservice architecture, a specific dataset is bound to a specific microservice. As a result — a clear schema boundary is dictated when the microservice is built.

If you need to replace your database solution, you only have to migrate a smaller, clearly defined dataset. It’s easier to grasp what needs to be done. You can understand what the microservice does simply by looking at the data it holds. The number of clients that can talk to the database is reduced to 1 — the microservice. All other clients must access the data through APIs exposed by the microservice, so changing database implementations becomes more of a possibility.

A few months ago, I replaced a Cassandra database with MySQL in a microservice. I had good reasons. It wasn’t easy, but it was doable. This feeling of “I can do this” will allow your developers and DBAs to go faster.

Understanding Domain Driven Design

Let’s face it, understanding domain-driven design can be challenging. Many books were written, and there are still some disagreements within the DDD community on certain aspects what “correct” DDD should be.

DDD can become even more challenging when you’re looking at one big monolith. In a microservice architecture, it feels more natural to talk about the domain of a microservice, because a microservice serves a single bounded context.

Does this mean that microservices directly map to a domain? No. DDD existed long before microservices was a thing. DDD allows you to think about your business requirements, and agree on terminology used by your organisation. It just so happens that sometimes the domain could end up as its own microservice. Or not. The relationship is not one-to-one. You can, and should, have Domain-Driven Design in your monolith as well.

Benefits for line of business

Using microservices, a business can invest in what matters today, without having to worry on how it impacts the entire application. Need a new search capability? Let’s develop that, in isolation. Need to improve your analytics? Let’s invest in that. The competition just released a cool new feature that we don’t have? Let’s address that feature, in isolation. The ability to limit the scope of a feature request to a few components of the larger system allows the business to go faster.

There are no silver bullets

Microservices have organisational benefits for the development and business teams. Yet, it’s no surprise that the drawbacks extend to the human factor as well. Eventually, you are building a single logical application. You need to properly communicate between microservices. Interfaces become the critical component. Lack of engagement and collaboration between development teams would lead you down the wrong path very quickly.

Then there’s the concern of breaking your system into too many microservices. As Matt Stine recently said:

Don’t go crazy out there. The purpose of microservices is to help your organisation develop software quickly and deploy it easily. If you can’t tell the forest from the trees you’re missing the point. In some cases, it is possible that your technological requirements will contradict your business requirements. The business wants a well organised system with clear boundaries. If you get so fine-grained to the point where every microservice has to call some other microservice to fulfil its duties, you’re creating a huge network of systems, which probably doesn’t benefit anyone.

CQRS is a good example for that. It’s a design pattern that suggests you should separate your writes from your reads. This allows you to scale reads and writes separately, as needed. That is a good, technological benefit. What about the business? Does it really benefit the business that you now (potentially) manage two microservices instead of one? Does it mean you need two teams instead one? Do you add additional complexity that might not be needed for every use case? Perhaps simply throwing more compute resources at the problem would solve the same scaling needs but greatly simplify the development efforts?

I’m being a bit of devil’s advocate here, of course. There are use cases where I feel a CQRS approach makes a ton of sense. But there are cases where it may provide more harm than good. Sometimes technology requirements and business requirements collide. Tread lightly.

As a rule of thumb, I recommend that if you choose the path of microservices, start with a least amount of microservices to achieve your business requirements, and only break it further if needed at a later stage. It’s always easier to start with 2–3 mini-monoliths instead of 30–40 nano-services. It’s mentally easier for us to break 1 thing into 5 things than it is to merge 5 things into 1.

Another tendency we have is to create an overload of dependencies between components. It’s the easy solution at first glance. But the whole reason you chose microservices is to create standalone, loosely coupled services. If you create so many dependencies between them, you just add up the drawbacks of a monolith to the drawbacks of microservices. Congratulations, you just created a bigger problem than you had before.

Nobody wants a distributed monolith. Microservices have benefits and drawbacks. Monoliths have benefits and drawbacks. I find it very hard to see anything but drawbacks for distributed monoliths 😄.

Lastly — not everyone would be happy with the transition to microservices. Prepare for some unsatisfied developers. Some might even quit. It’s inevitable when you’re changing someone’s perception of software development so fundamentally. Invest in getting your teams excited about the transition. Educate them on the benefits and the drawbacks, both for the organisation and for their own personal development. Let the teams pick cool names that represent their development domain. Some developers will feel like they are going through a 12-steps program, from denial, to anger, to acceptance.

Conclusion

In this article I tried to explore the organisational and cultural benefits of moving to a microservice architecture.

This entire article could have been dismissed as irrelevant in a perfect world where all developers, QA engineers and DBA admins are top-notch, with perfect design that is always open for extension. In reality though, software development is hard. Architectures like microservices are meant to put guardrails to let development teams achieve better results.

On the other hand, I do not pretend that developing in microservices is always better. As Chris Richardson mentions in many of his talks, monoliths are not an anti-pattern. They are a good solution for some problem domains. Microservices are a good solution for other problem domains. Personally, I feel you should always start with a monolith and move to microservices when it makes sense. You’ll know you reached that point because you’ll probably feel the burden of complexity that was described in this article.

Always think about how architectural changes impact your business and development teams — will it improve or impair collaboration? Will my employees be happier when they go home? Will they be excited to come to work in the morning? Will this change get everyone moving faster, or will it create an even bigger complexity that the teams cannot manage?

In the end, software is created by people to serve people. Usually, the software that your organisation develops will match the structure of the organisation itself. Consider if microservices would make your organisation‘s software better, or worse.

Good luck, and happy coding!

My thanks to Oliver Drotbohm, Michael Gehard, Jakub Pilimon and Neven Cvetkovic for helping me improve this article