A big part of my work involves interacting between microservices using event sourcing.

There have been excellent design patterns evolving over the years to allow for truly decoupled microservices, be it event sourcing, CQRS, SAGA, or transaction log tailing. I recommend reviewing some of these patterns over at microservices.io if you are unfamiliar with them.

Problem

One challenge that I have faced is the need to achieve local transactionality when a microservice needs to perform multiple activities as an atomic operation. Although the SAGA pattern can solve the lack of distributed transactions by defining compensating events for failed transactions, it does not solve the problem of needing a local two-phase commit within the microservice itself.

For example, you cannot guarantee that a commit to Cassandra and a message delivery to Kafka would be done atomically or not done at all.

So the question is: how can I ensure ALL the activities I perform are being handled as a single transaction?

Example

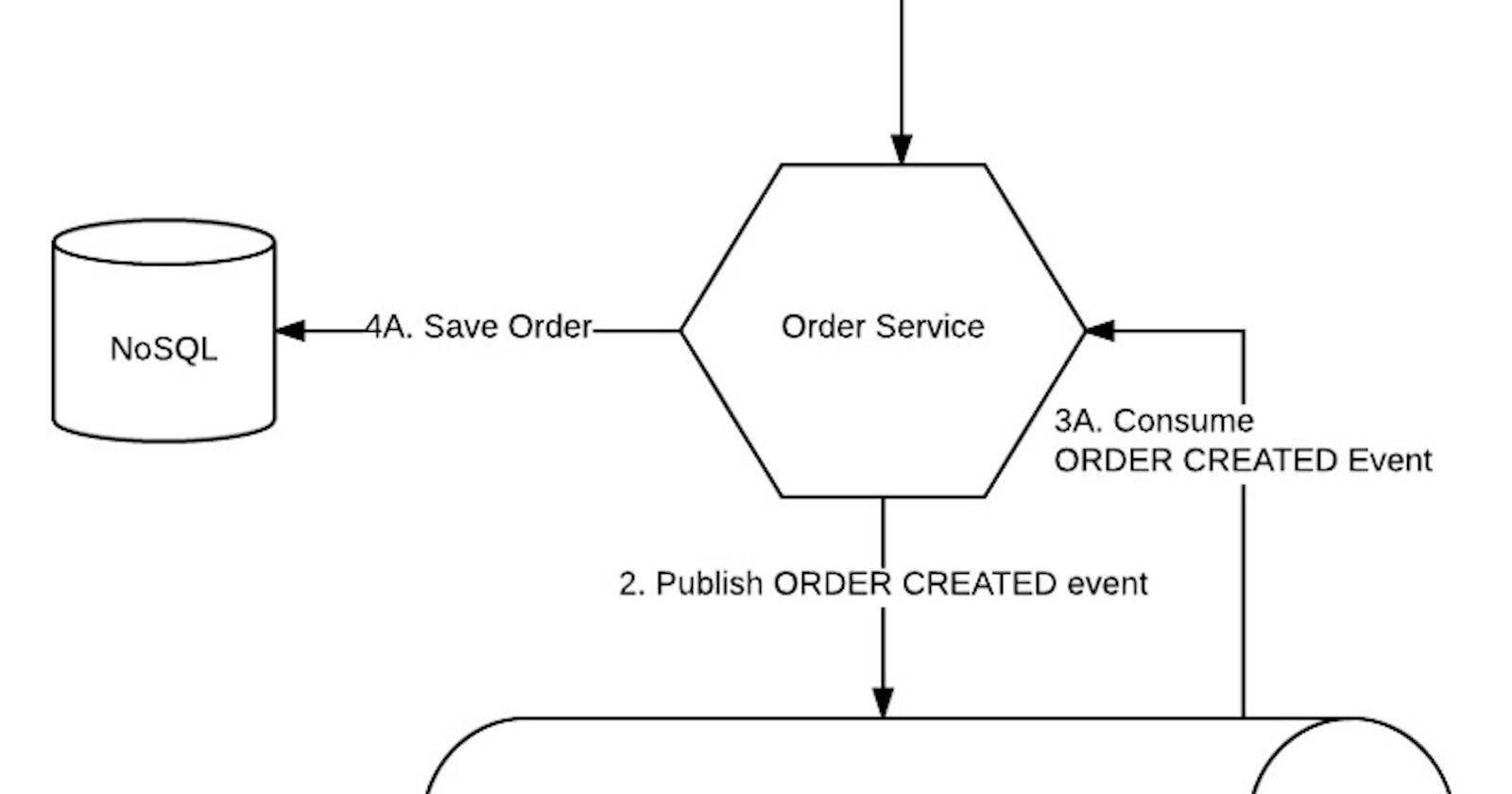

Let’s take a common use case: Updating a local NoSQL database and also notifying a legacy system of record about the activity. The scenario is as follows:

- You broke away an Order Service from a legacy monolith.

- Your clients are still in transition from the monolith to the microservice, and therefore you still need to maintain consistency with the monolith system of record.

- For simplicity of the diagrams, I’m not mentioning the NoSQL records being in PENDING state at the beginning of the flow and moving to COMPLETE state in the end, although this is ofcourse highly encouraged in the SAGA pattern.

Forces

- Two phase commit is not possible.

Option 1: Directly interacting with the system of record

The problems with this architecture are immediatly clear:

- You have tight coupling between your microservice and the system of record. This dependency would make it hard to remove the feature from the monolith (“strangle the monolith”), since you would need to update both the monolith and your microservice. Additionally, your Order Service is not self-contained, and has to be aware of the existence of the monolith.

- What happens if you are able to commit the transaction in step 2, but the server crashes before completing step 3? You are now faced with data inconsistency/corruption in your system.

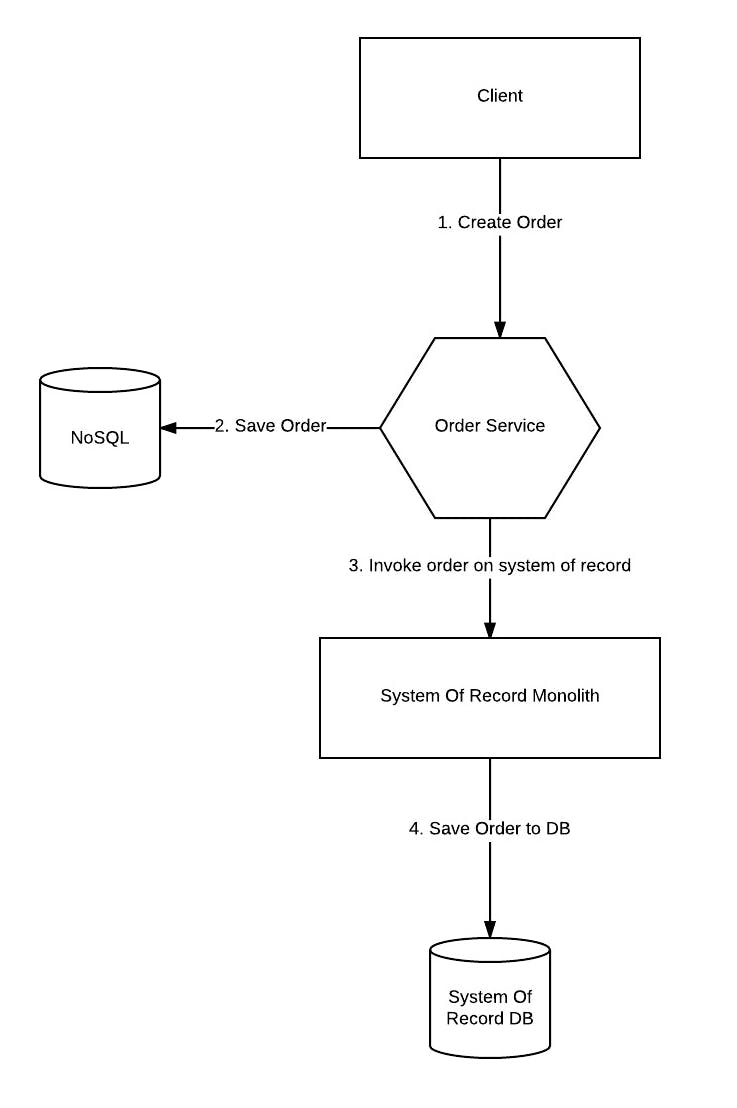

Option 2: Decouple the system of record using a message broker

With this option:

- You are decoupling the system of record from the microservice by using a message broker and a publish/subscribe model.

- A dedicated event processor (“Legacy Handler”), which may be part of the monolith or a seperate, dedicated microservice, handles the interaction with the system of record only.

- Once the transition to the Order Service is fully complete, you can simply decomission the Legacy Handler microservice without any code changes.

- The Order Service is unaware of the system of record and the system of record is unaware of the Order Service.

- You can design compensating events generated by the Legacy Handler in case a failure occurs while updating the system of record. That way, you make sure both systems are in sync.

This is usually as far as most event sourcing/SAGA pattern diagrams go from what I’ve seen.

However, there is still a concrete problem: How do you guarantee atomic execution of both the NoSQL writes and the publishing of the event to the message broker?

- The Order Service may save the order to the NoSQL database (#2), but crash before sending the message to the message broker (#3).

- If we were to reverse the order, the problem still persists: The Order Service may send an event to the message broker, and crash before saving the data to the NoSQL database.

- The problem also exists in case of other errors during the execution: If the message broker is unavailable for some reason, your service in at an inconsistent state and you’ll need a compensating transaction on the NoSQL database.

- If you were to publish before saving to database, the issue still exists — you could successfully publish to the message broker but fail on writing to the DB. You would then have to send a compensating transaction to the message broker. What happens if the message broker is now unavailable?

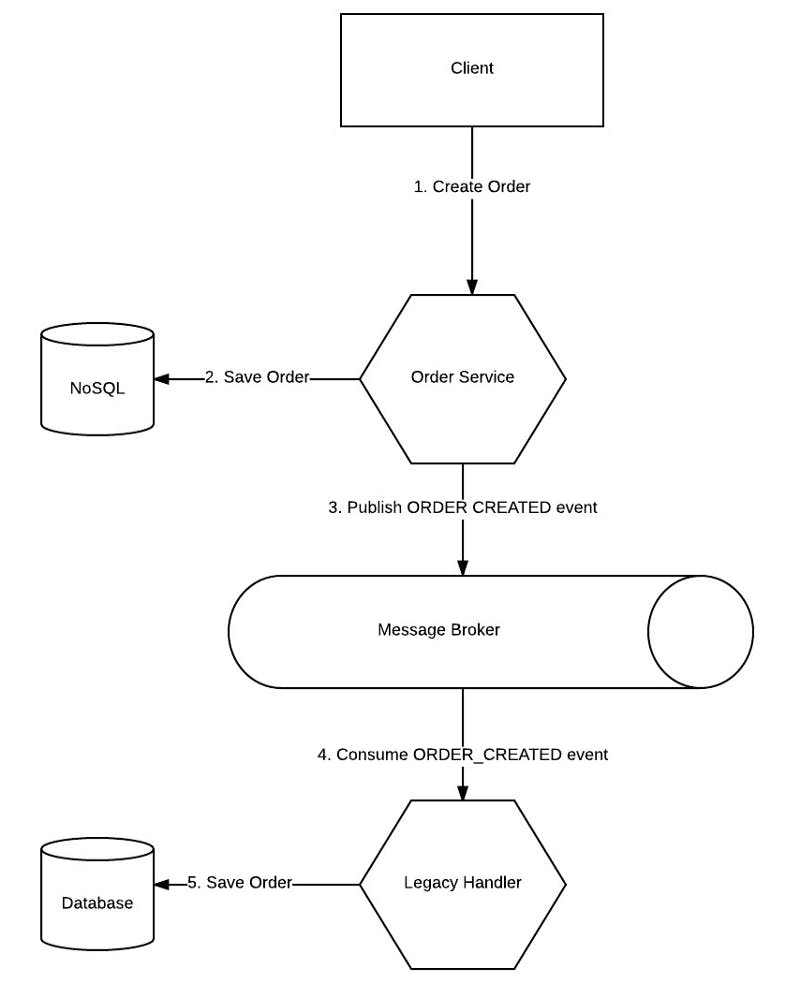

Option 3: Listen to Yourself

This brings us to the “Listen to Yourself” design pattern.

In this example, the Order Service publishes the ORDER_CREATED event to the message broker, but also consumes ORDER_CREATED events, just like the Legacy Handler. This basically means it is “listening to itself”, meaning it consumes the messages that it itself produced. Now the Legacy Handler and the Order Service are processing the writes to their respective databases in parallel and can guarantee the success of the business transaction, or its synchronized failure with compensating events.

Resulting Context — Benefits

- You achieve atomic transactionality. If the message was published to the message broker, you assume a consistent state.

- If the Order Service crashed before publishing to the message broker, the database would not be updated and the client will simply receive a 500 error.

- If the Order Service crashed after publishing the message, the data is still protected. Eventually, the message will be processed by the Order Service, either by a different instance that is registered to those events or by the instance the crashed (once it is restarted). The message broker guarantees the message delivery.

- If the message broker itself is unavailable to publish the message, nothing is written to the NoSQL database and an error is returned to the client.

- If the message broker crashed after receiving the message, the message was already persisted to disk and will be served once the message broker is back online.

Note: Potential duplicate messages are always a possibility with a message broker so you should design your message handling to be idempotent regardless of the solution you choose.

- You gain better performance because the client no longer waits for both message delivery and writing to the database. The response can be returned immediately once the acknowledgement from the message broker has been received.

- You can easily design compensating transactions since you can enforce the order of messages in the topics. Using a partitioned message broker such as Apache Kafka, you can guarantee that a compensating transaction would be sent to the same topic/partition as the topic that created the original event. This means that the Order Service would only process the compensating transaction after it finished processing the write to the NoSQL database. This means less code to manage the state of the database.

- Using the message broker gives you access to excellent frameworks such as Spring Cloud Stream, that offer a built-in retry mechanism. You can configure a backoff policy with an ever-growing interval between attempts to mitigate most network unavailability issues with the database. It also allows the messages to automatically move to error/DLQ topics if a message is deemed impossible to handle. Monitoring solutions can track the items in the error queues, which would provide clear visibility to DevOps teams. All this means — less code you have to write to manually manage retries and error handling.

Resulting Context — Drawbacks

- This style of programming can be unfamiliar and requires your application to be event driven.

- All your events and database writes must be idempotent to avoid duplicate records.

- The client will not receive feedback about the actual write to the database. There may be business errors while persisting the transaction that the client should be aware of.

- The client isn’t guaranteed to read their own writes immediately. That is because the writes to the NoSQL database will only be done after the response is returned to the client. While this is a known drawback of Eventually Consistent applications, this pattern makes it even more extreme, since the local database itself is also inconsistent when the transaction is complete. Caching solutions can mitigate that, although that would add additional complexity.

Related Patterns

The transaction log tailing pattern can achieve similar results to those described here. Your transactions will be atomic without resorting to two phase commit. The transaction log tailing pattern has the added benefit of guranteeing your database is committed before returning a response to the client.

Ofcourse, the transaction log tailing pattern has its own set of drawbacks. As mentioned here, some of them are:

- Relatively obscure

- Database specific solutions

- Low level DB changes makes it difficult to determine the business level events

- Tricky to avoid duplicate publishing

The first 3 items in this list can potentially be resolved by the Listen to Yourself pattern — your business events are high level and clear, and there is no need to rely to specific database solutions.

I would add the following considerstions for the comparison:

- Transaction log mining can sometimes feel like “magic code”, since events are produced in the system without your control. I try to avoid these if possible.

- Log mining solutions can be closed source and incur licensing costs (such as Oracle Golden Gate), or be open source but unsupported by the database vendor (such as Linkedin Databus).

In this article, I presented a simple but powerful approach for event sourcing. It has probably been implied in various other design patterns, but I believe it is important enough to stand on its own.

Good luck, and happy coding!